Trees

The benefits of trees and tree canopy

Here’s some more information on the benefits of trees and tree canopy to our community, to individuals and to the environment.

For further reading, there are a number of Victorian and local governments’ own references that support these benefits. Check these three links amongst the many:

Trees for cooler and greener streetscapes

Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (monlib.vic.gov.au)

More trees for a cooler greener west (environment.vic.gov.au)

The government’s own website, planning.vic.gov.au, focuses on “Increasing tree cover in urban streets”. It says:

Data and mapping indicate on average Melbourne’s urban areas are over 8°C hotter than non-urban areas.

Streets are typically ‘hardscapes’, paved environments with limited greenery, that:

- exacerbate the urban heat island effect

- create excess stormwater runoff

- negatively impact human and ecological health due to a lack of trees and other vegetation.

Because urban streets have many different uses it can be challenging to plan and design streetscapes that prioritise trees. Trees compete for space with overhead powerlines, underground infrastructure, street furniture, and movement pathways and sightlines for pedestrians, cyclists, motorists and public transport. Ensuring adequate irrigation can also be difficult without the right designs in place.

Despite these challenges, it is vital we maintain our urban trees and grow more to provide shade, cool the city and enable us to cope better in extreme heat.

Benefits to our community

Helping to negate the increased Urban Heat Island effect from Global Warming

The cooling effect of trees is our best weapon to counter the impact of global warming on our quality of life, so important now with average temperatures predicted to increase in the future due to climate change.

Figure 1: The Cooling Effects of Trees

Paired aerial and thermal imagery.

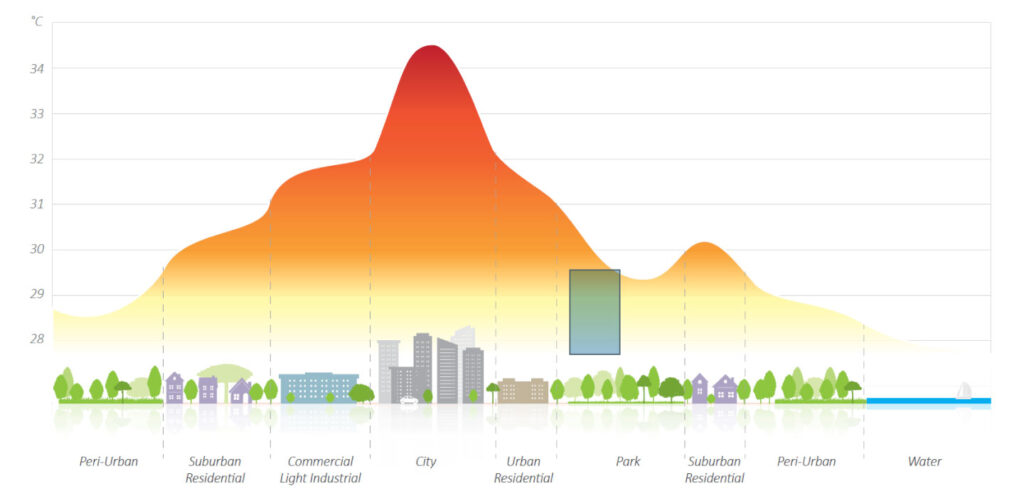

Tree shade and its beneficial cooling effect has always played an integral part in promoting a community’s outdoor activities and lifestyle choices. Whilst UHI was originally considered on an urban versus rural scale, with improved thermal imaging data, we can easily see the direct correlation between tree canopy and lower infrared (radiant heat) emissions (above). The schematic in Figure 2, below, provides a graphic of how the UHI and its associated temperatures might vary across different urban scenarios.

Figure 2: The Urban Heat Island Effect (adapted from McDonald et al. 2016)

Water runoff, erosion, drainage infrastructure and flooding

Extremes in our weather are increasing with both more droughts and more floods forecast. We are now seeing “once in a thousand year” events and multiple what-used-to-be “one in a hundred year” events in relatively short periods. In our transition from a naturally vegetated landscape to a built environment with large areas of hardscape surfaces (buildings, roads and footpaths), we have created challenges for stormwater management. In rural environments, tree root systems no longer absorb moisture from, and physically stabilise, the soil. Both scenarios create increases in surface water run-off, which result in flash flooding, erosion, and waterway pollution. Apart from the massive damage done and the enormous cost to the community of repairing damage, we also need to fund the building of larger drainage systems.

Local economies, community wellness, health-care costs and crime

Numerous papers detailing and dimensioning the community-related benefits coming from human interaction with trees include things like:

- Community cohesion and socialising

- Reduced healthcare costs through faster recovery times

- Reduced crime rates

- Increased retail and tourism through placemaking, beautification, and shopper dwell times

These relate to the enhanced amenity and aesthetics of areas associated with trees.

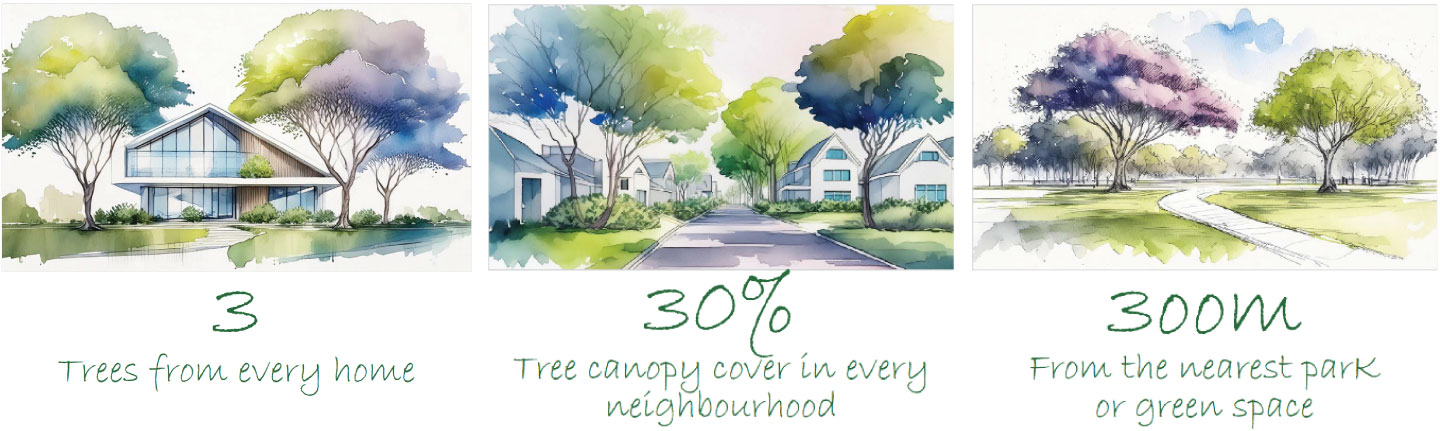

Because of the benefits above, best practice urban design and town planning now incorporates the concept of ‘Green Infrastructure’ and “rules” such as “3, 30, 300” to provide social equitability across communities through readily accessible, treed, greenspaces.

Here are a sample of the many references that support the points above:

Adams, M. A. and Smith, P. L. (2014). A systematic approach to model the influence of the type and density of vegetation cover on urban heat using remote sensing. Landscape and Urban Planning Volume 132, December 2014, Pages 47–54.

Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, Finkelstein EA, Katzmarzyk PT, van Mechelen W, Pratt M. (2016). The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet. 2016 Sep 24;388.

Gilstad-Hayden, K and S. Meyer. (2015). Greater tree canopy cover is associated with lower rates of both violent and property crime in New Haven, CT. Landscape and Urban Planning.

Nguyen, T. and Morinaga, M. (2023) Effect of roadside trees on pedestrians’ psychological evaluation of traffic noise. Front. Psychol. 14:1166318.

Pataki, D.E., Alberti, M., Cadenasso, M.L., Felson, A.J., McDonnell, M.J., Pincetl, S. (2021). The benefits and limits of urban tree planting for environmental and human health. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9.

Rosenfeld, A. H., H. Akbari, J. J. Romm and M. Pomerantz (1998). Cool communities: strategies for heat island mitigation and smog reduction. Energy and Buildings 28(1): 51-62.

Tarran, J. (2006). Trees, Urban Ecology and Community Health. TREENET Proceedings of the 7th National Street Tree Symposium:7th and 8th September 2006, Adelaide, TREENET Inc.

Wolf, K. (2003). Ergonomics of the City: Green Infrastructure and Social Benefits. Engineering Green: Proceedings of the 2003 National Urban Forest Conference, Washington D.C.

Xiao, Q., E. G. McPherson, J. R. Simpson and S. L. Ustin (2006). Hydrologic processes at the urban residential scale. Hydrological Processes 21(16): 2174 – 2188.

Benefits to individuals

There are direct and indirect benefits for households and individuals associated with tree canopy. These generally relate to the enhanced amenity and aesthetics of the trees themselves, the shade they cast and localised cooling from transpiration. Some of these have been dimensioned economically and some have been recognised strategically such that they form recommendations in urban forest strategies. They include:

- Improved health and well-being

- Increased property values

- Electricity savings due to shade, especially over houses and air conditioners

- Water saved by reduced electricity usage

- Reduced skin cancer risk through shading walkways, especially to schools

It is known that areas and streets with relatively more trees have higher real estate values (Wolf. 2007).

The increased shade provided by trees in urban environments has a direct, measurable impact on household energy costs which have increased dramatically in recent years.

In addition to the links above, here are a sample of the many references that support the summary points listed:

Akbari, H., Pomerantz, M., & Taha, H. (2021). Cool surfaces and shade trees to reduce energy use and improve air quality in urban areas. Solar Energy, 70(3), 295-310.

Astell-Burt T, Feng X. (2019). Association of Urban Green Space with Mental Health and

General Health Among Adults in Australia. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(7): e198209. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2019.8209.

Wolf, K. (2007). City trees and property values. Arborist News (August): 34-36.

Benefits to the environment

Trees provide substantial environmental benefits, sometimes referred to as “eco-system benefits”. These include carbon sequestration and storage and improved air quality in urban environments through their ability to remove nitrous oxides and other pollutants.

Critically, they provide flora and fauna habitat and the opportunity for enhanced biodiversity in the broader environment. Not only do they provide nesting places hollows for birds (Figure 1) but for sugar gliders and more. Even when they’ve fallen over or into waterways, they provide homes for lizards and fish.

Best practice urban planning now includes the concept of treed fauna corridors to facilitate both habitat creation and diversity.

Figure 1: Even dead trees have value; providing hollows for birds such as budgerigars

Here are some references for further reading:

Alvey, A. A. (2006). Promoting and preserving biodiversity in the urban forest. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 5, 195-201.

Bolund, P. and S. Hunhammar (1999). Ecosystem services in urban areas. Ecological economics 29:293-301.

Gibbons P. and Lindemayer D. (2002). Tree hollows and Wildlife Conservation in Australia. CSIRO Publishing.

McPherson, E. G. (2008). Urban Forestry and Carbon. Arborist News 17(6): 31-33.